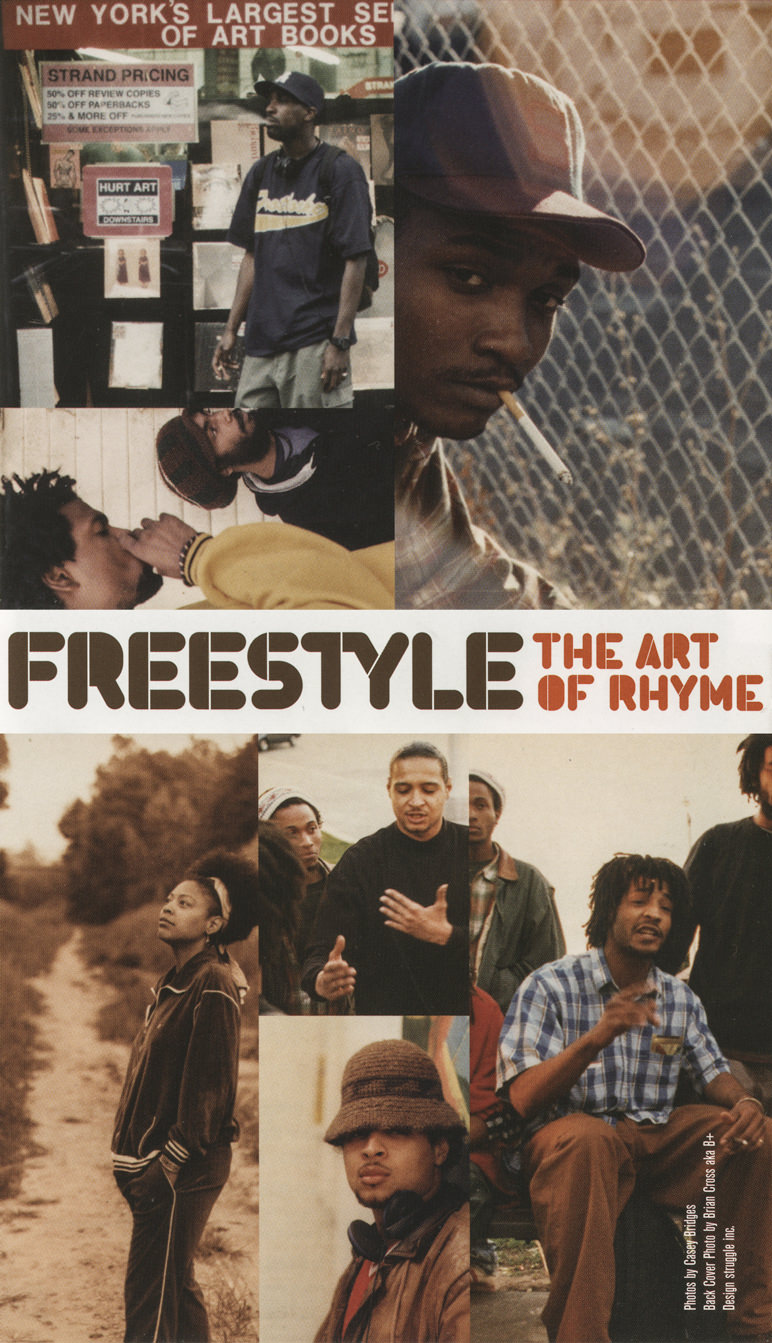

Freestyle: The Art of Rhyme

Liner notes to DVD release of documentary film

Like a needle to the record and a pen to papyrus, Kevin Fitzgerald’s camera in his Freestyle: The Art of Rhyme penetrated and saw into hip-hop worlds that were visible but unseen. Just as on “Triumph,” where the Wu Tang Clan’s Masta Killa raps that his rhymes “give sight to the blind,” Freestyle gives in-sight to a world where words become windows into other worlds. While the film itself powerfully explores the art of improvisation in hip-hop, Freestyle is also an incredible aesthetic work. And it is no wonder that the opening credits identify it as a film by DJ Organic (aka Kevin Fitzgerald), because Freestyle is in essence a cinematic mix-tape. For one, it was rare to see the same version of the film at various festivals throughout the world from Europe, South America, North America and Africa. Not because the film needed to be reworked, but because Organic brought a DJ’s ethic to the cinema screen, creating various remixes for different audiences by digging into his vast crate of visuals. Using images as dubplates and obscure archival footage as samples, Organic blended, cut and remixed the different film stocks, color and black and white images, incredible interviews, rare battle footage and the immediacy of hand held shots of freestyle ciphers like all dope selectahs do on the decks. His guerilla filmmaking style and use of different aesthetics may seem disorienting to some – but that’s the point. Hip-hop was meant to shake shit up and to overturn the status quo. I mean, who else in the United States could turn an abandoned building or a subway train into a canvas, a piece of cardboard into a dancefloor, turntables into instruments, and old records into new sounds? Who else besides black and brown people in post-COINTELPRO America had the courage, the creativity and the necessity to reclaim and remix not only their environments, but also their very existence?

And just like hip-hop is deeply rooted within various Afro-diasporic traditions – what Amiri Baraka called the “changing same” – Organic and Freestyle follow in the tradition of the “L.A. School” of independent Black filmmakers that emerged out of UCLA in the 1970’s, such as Haile Gerima, Charles Burnett, Julie Dash, Larry Clark and Ben Caldwell – all of whose films were influenced by radical politics, Third World cinema and a desire to challenge Hollywood’s degrading images of Black people. Freestyle continues the legacy and spirit of that movement, but especially Larry Clark’s classic underground film Passing Through (1977), which used Los Angeles as its backdrop to poetically explore the relationships between jazz music, the underground, Black creative genius and its relationship to an exploitative record industry. Sound familiar? It should, because Freestyle is not the Hollywood fantasy of whitewashed hip-hop and MC battles seen in 8 Mile, or the hip-hop now used by the military in its campaigns to recruit ghetto youth to pick up guns for Charlie Company. No. Freestyle presents hip-hop that challenges MTV minstrelsy and BET blackface by giving us a window into the seemingly bygone era of early ‘90’s boom bap, a celebration of the underground on both coasts before the advent of hip-pop – from KDAY, the Good Life Cafe and Project Blowed in Los Angeles (don’t forget UNITY!) to Washington Square Park and the emergence of Lyricist Lounge in New York. Without a narrator, Freestyle tells hip-hop history from the perspectives of those who participated in its making – from the rhetorical rebellion of street corner ciphers, to the Last Poets, Crazy Legs, Bobbito and Medusa, and on to the legendary battles between Supernatural, Craig G and Juice.

From the sacred to the secular and the from the studio to the street corner, Organic’s film is a celebration of freestyle in all of its possibilities – not just as an MC, DJ or B-Girl – but as an ethos, a complete way of being. But just like during the jazz era (and today for that matter), when critics elevated and affirmed white standards of art by incorrectly viewing improvisation and playing off the head as simply a product of instinct and not intellect, and passion not purpose, Freestyle reveals what power has concealed – that creative genius arises out of the necessity for survival, as spontaneity and improvisation have become not only acts of resistance, but in many ways the defining feature of blues peoples throughout the world, from Baghdad to Brooklyn. Like Wild Style before it, Freestyle captures much of the energy and intensity, and the power and protest that forms the break of hip-hop culture, and though it may be too late to now talk of hip-hop and possibility in the same breath, Organic’s film provides a glimpse into what that might sound like.