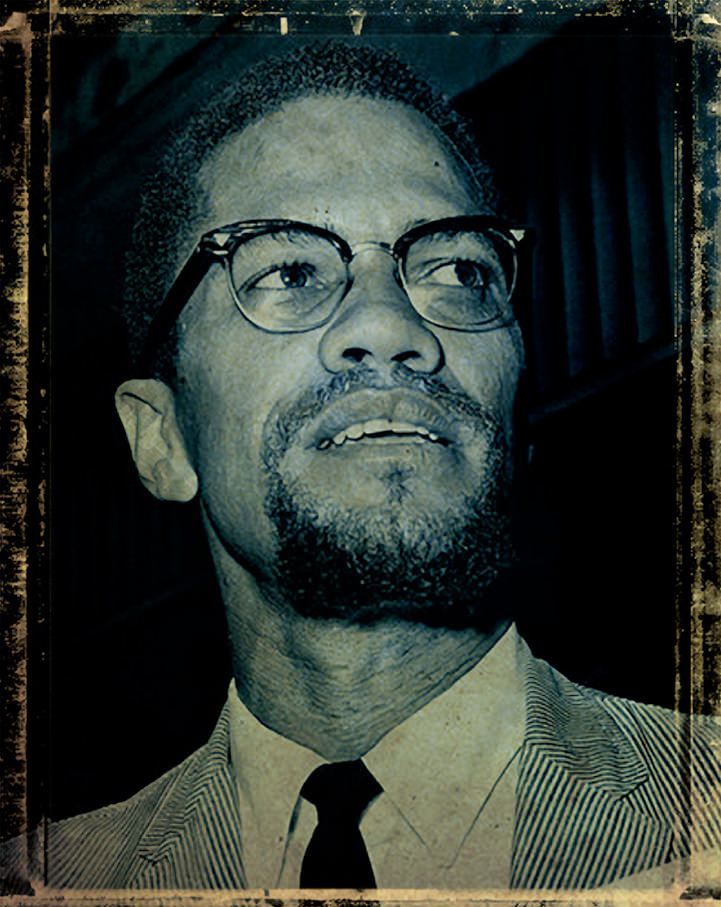

Respect the Architect: Malcolm X, the Elections and the Politics of Empire

Excerpt from Al Jazeera

With Guantanamo still open, drones still killing and anti-Muslim sentiment forming the rumbling bass line of empire, the upcoming U.S. Presidential elections have once again raised the specter and threat of Islam and the Muslim Third World to U.S. national security and its interests. And with Obama as one of the two major candidates, the issue of Blackness is the elephant in the room.

While many want to further stigmatize Obama as a “closet Muslim” and the “Arabian Candidate” of the 21st century, others see his Blackness as rebranding the image of America and helping to further U.S. interests in the Muslim Third World through a new “post-racial” and benevolent veneer. But as I detail in my recent book, these relationships and histories between Blackness, Islam and the Muslim Third World are not new in the United States. In fact, it is Malcolm X who has come to define these converging histories, and it is his legacy that is in many ways causing so much national anxiety in a post-9/11 United States with a Black president who’s middle name is Hussein.

For to be Black in America is enough to be deemed un-American, but to be Black and Muslim is to be anti-American. While the “smearing” of Obama as a Muslim in the post-9/11 climate is informed by the threat posed by that thing called “Al-Qaeda,” Obama’s Blackness and his “proximity” to Islam is really a deeper seated anxiety around Malcolm X, who challenged American authority over not only the Black past but also a Black future, demanding that Black people view themselves not as a national minority but as part of a global majority.

For Malcolm X, “Islam was the greatest unifying force of the Dark World,” and the Muslim Third World had a defining impact on Malcolm X’s life and political vision, whether it was the spiritual center that was Mecca or the anticolonial struggles in Egypt, Algeria, Palestine, Iraq and elsewhere. But for Malcolm one didn’t have to be a Muslim. What was important was the recognition of a racial reality to one’s secular suffering that would view white supremacy as a global phenomenon and link Black struggles with those in the Third World.

But there has been a persistent demand to contain and even erase the possibility of Black internationalism in the United States. As a fulfillment of the Civil Rights tradition, Obama’s presidency has symbolically suggested that not only do Black people have a stake in this country, but that the feeling is mutual – as his status as “leader of the free world” seeks to wed Black identification with America, its power and its destiny.

Originally published on 11.04.2012 in Al Jazeera.